Sudden Cardiac Death: What You Must Know and What to Do

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) happens when the heart stops beating unexpectedly. It can strike people with known heart problems and those who seem healthy. The good news: you can reduce the risk by knowing the warning signs, checking medicines, and getting the right tests.

What raises the risk?

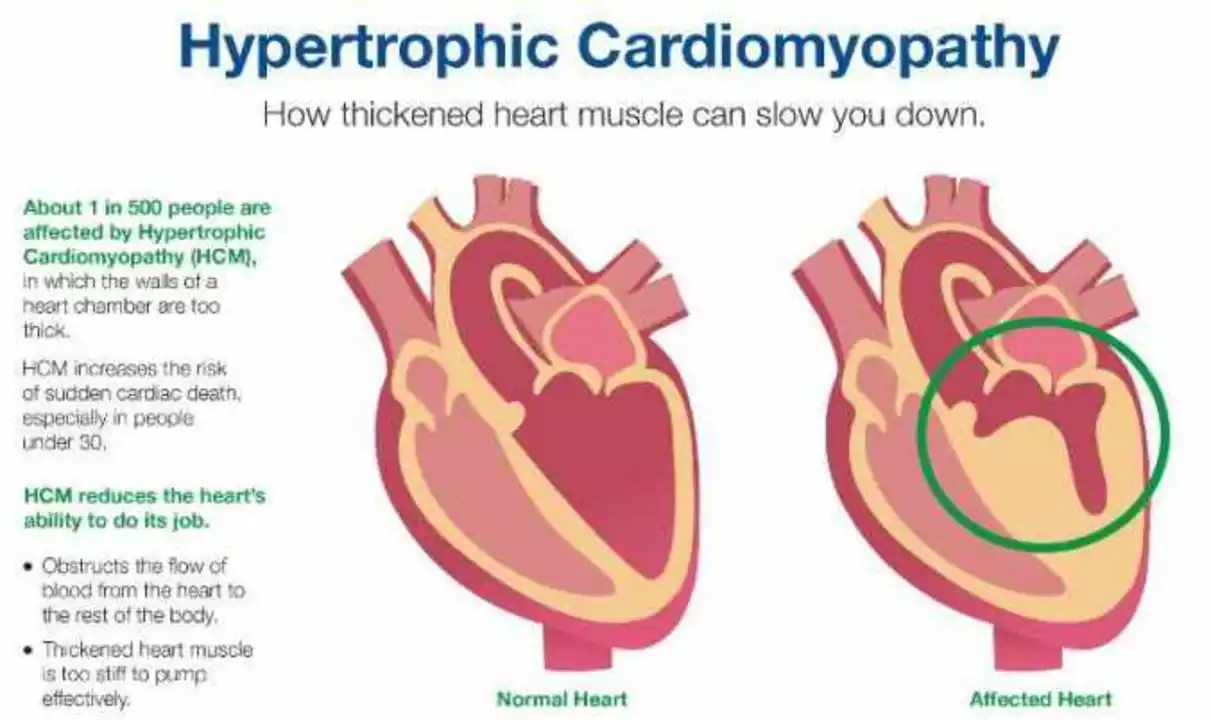

Several things make SCD more likely. Coronary artery disease and prior heart attacks top the list. Weak heart pumps (reduced ejection fraction), cardiomyopathies, and electrical disorders like long QT syndrome or Brugada syndrome also raise risk. Age, uncontrolled high blood pressure, diabetes, and sleep apnea add to the danger. Don’t forget reversible causes: low potassium or magnesium, fever, and stimulant use (cocaine, amphetamines) can trigger deadly arrhythmias.

Some medications can increase SCD risk by prolonging the QT interval or causing other rhythm problems. Examples to watch for include certain antidepressants (like high-dose citalopram/Celexa), some cancer drugs (nilotinib), older antimalarials and some antibiotics. If you take any prescription drug, ask your prescriber whether it affects your heart rhythm and if an ECG is needed.

What to watch for and immediate steps

Warning signs aren’t always dramatic, but take them seriously: fainting or near-fainting during activity, repeated palpitations, unexplained shortness of breath, or chest pain. If someone collapses and is unresponsive, call emergency services, start CPR if trained, and use an AED if one is nearby. Fast action saves lives.

For people with symptoms or a family history of sudden death, the checklist is simple: get an ECG, a heart ultrasound (echocardiogram), and possibly a 24–48 hour Holter monitor. If tests show problems, your cardiologist may suggest further testing—stress tests, genetic testing, or electrophysiology studies.

Prevention focuses on removing risks you can change. Review all medicines with your doctor or pharmacist. Keep electrolytes normal—especially if you’re on diuretics. Treat high blood pressure, diabetes, and sleep apnea. Avoid illicit stimulants and limit heavy alcohol. For people at very high risk, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) can prevent sudden death by shocking the heart back to a normal rhythm.

Want a practical first step? Ask your primary care clinician for an ECG if you have fainting spells, a family history of sudden death, or if you’re starting a drug known to affect heart rhythm. That small test often reveals problems early and leads to simple fixes.

If you have questions about specific medicines or tests you’ve read about on this site, talk to your provider. Every case is different, and a quick medical review can help you sleep easier.

May, 9 2023

May, 9 2023