When you take more than one medication, your body doesn’t treat them like separate events. It processes them together - and sometimes, one drug can mess with how another moves through your system. This is called a pharmacokinetic drug interaction. It’s not about how the drugs feel or what they do to your symptoms. It’s about how your body absorbs, distributes, breaks down, or gets rid of them. And when this goes wrong, it can lead to serious side effects - or make your medicine stop working altogether.

How Your Body Moves Drugs Around (ADME)

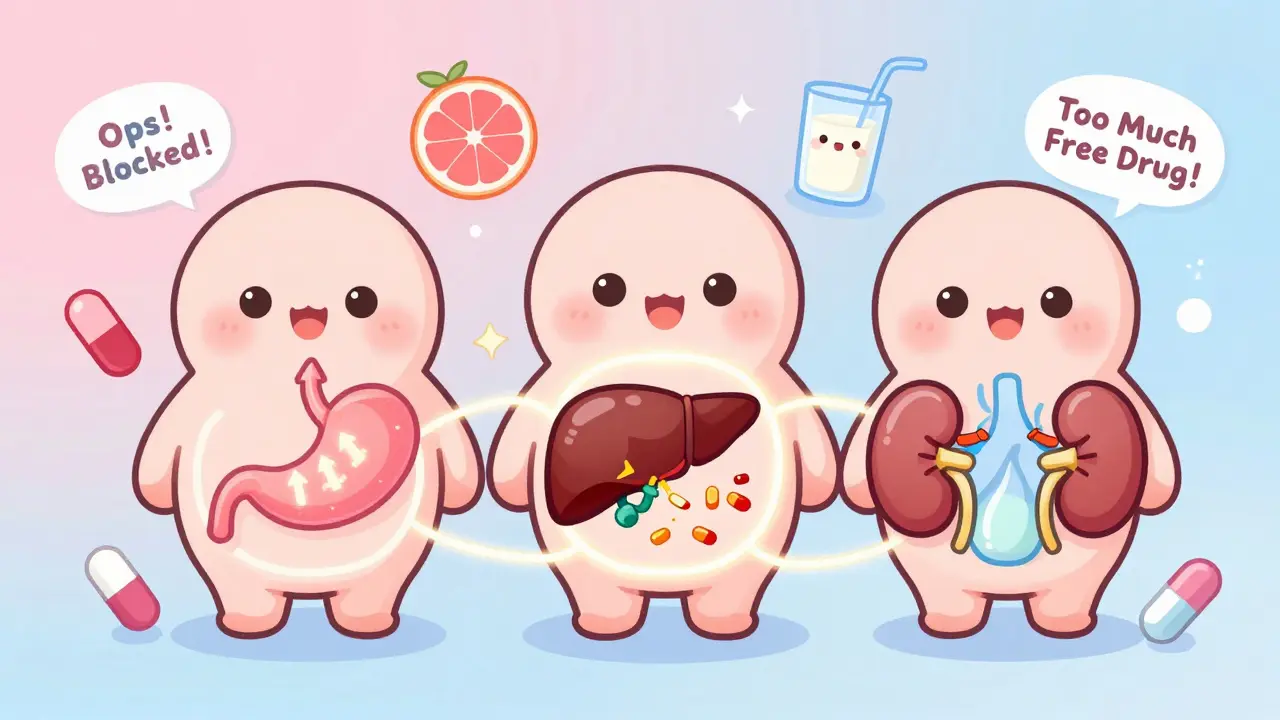

Your body handles every drug through four main steps: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion. Think of it like a delivery system. First, the drug gets into your bloodstream (absorption). Then it travels to where it’s needed (distribution). Your liver breaks it down (metabolism). Finally, your kidneys flush it out (excretion). If one drug interferes with any of these steps, the amount of the other drug in your system can go too high or too low.

This isn’t theoretical. In the U.S., drug interactions contribute to about 6-10% of hospital admissions among older adults, according to the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. And with more than half of Americans taking at least one prescription drug - and nearly 20% taking five or more - these interactions are a real, everyday risk.

Absorption: When Drugs Block Each Other’s Entry

Some drugs need your stomach acid to be absorbed properly. If you take an antacid, proton pump inhibitor, or even calcium supplements at the same time, they can neutralize that acid and stop the drug from entering your bloodstream. For example, ketoconazole - used for fungal infections - won’t work if taken with heartburn meds. The fix? Space them out by at least two hours.

Another common problem happens with antibiotics like tetracycline. If you take it with milk, yogurt, or calcium supplements, the calcium binds to the antibiotic and forms a hard-to-absorb complex. Studies show this can cut absorption by up to 50%. Same goes for iron pills and dairy. The solution? Take these medications at least two to three hours before or after dairy or calcium-rich foods.

Even opioids can slow down how fast other drugs like acetaminophen get absorbed. It’s not about pain relief - it’s about timing. Your body’s digestive system is a delicate balance, and one drug can throw it off.

Distribution: When Drugs Fight for a Ride

Most drugs don’t float freely in your blood. They hitch a ride on proteins - mainly albumin. But if two drugs want the same protein spot, one can push the other off. This is called displacement. The displaced drug becomes “free” and active in your system - and suddenly, you get more of it than intended.

The classic example is warfarin, a blood thinner. If you take it with diclofenac (an NSAID for pain), the diclofenac kicks warfarin off its protein carrier. That can cause your blood to thin too much, leading to dangerous bleeding. This is why warfarin is one of the top three drugs involved in serious interaction-related ER visits, according to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices.

But here’s the good news: displacement doesn’t always cause problems. Your body usually adjusts by breaking down the extra free drug faster. The risk is only high if the drug has a narrow therapeutic index - meaning the difference between a safe dose and a toxic one is tiny. Warfarin, digoxin, and phenytoin are in that high-risk group.

Metabolism: The Liver’s Role - And Why Grapefruit Juice Matters

This is where things get serious. Most drugs are broken down by enzymes in your liver - especially a group called cytochrome P450. The most important ones are CYP3A4 and CYP2D6. If one drug blocks (inhibits) or speeds up (induces) these enzymes, it changes how fast another drug gets cleared from your body.

Inhibition means the drug sticks around too long. For example, clarithromycin (an antibiotic) blocks CYP3A4. If you take it with midazolam (a sedative), your body can’t break down the sedative fast enough. Result? You could fall into a deep, dangerous sleep or even stop breathing.

Another big one: grapefruit juice. It doesn’t just affect one drug - it affects about 85 prescription medications. Why? It blocks CYP3A4 in your gut. That means more of the drug gets into your bloodstream. Statins like simvastatin, blood pressure meds like felodipine, and even some anti-anxiety drugs can become toxic when taken with grapefruit. The FDA says you should avoid grapefruit entirely if you’re on one of these drugs.

Induction is the opposite. One drug tells your liver to make more enzymes - so it breaks down another drug too fast. St. John’s Wort, a popular herbal supplement for depression, is a powerful inducer of CYP3A4. If you take it with birth control pills, the pill might not work. If you take it with cyclosporine (a transplant drug), your body might reject the new organ.

Even common meds like fluoxetine (Prozac) can inhibit CYP2D6, affecting drugs like metoprolol (a beta-blocker). Studies show this can double the concentration of metoprolol in your blood - enough to cause low heart rate or dizziness.

Excretion: When Your Kidneys Get Overloaded

Your kidneys are your body’s trash disposal. But if two drugs use the same cleanup route, they can clog it. Probenecid, used for gout, blocks the kidney’s ability to flush out certain antibiotics like cephalosporins. That leads to higher levels - and possibly kidney damage.

NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen can do the same to methotrexate, a drug used for rheumatoid arthritis and some cancers. When these two are combined, methotrexate builds up and can cause severe bone marrow suppression.

Then there’s P-glycoprotein - a transporter that kicks drugs out of your kidney and gut cells. Itraconazole (an antifungal) blocks this pump, which means digoxin - a heart drug - stays in your body longer. That can cause dangerous heart rhythms. Digoxin is another top-three interaction risk drug, along with warfarin and insulin.

Real-World Stories: What Happens When Things Go Wrong

An 85-year-old woman was prescribed venlafaxine for depression and propafenone for heart rhythm issues. Both are broken down by CYP2D6 and transported by P-glycoprotein. When taken together, her venlafaxine levels spiked. She developed hallucinations and agitation - symptoms that looked like dementia but were actually a drug interaction.

Another case: a patient on lamotrigine (for epilepsy) started taking phenobarbital (a seizure drug). Phenobarbital triggered liver enzymes that turned lamotrigine into toxic metabolites. The result? Severe drops in white blood cells and platelets - a condition called leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. Both cases were preventable.

How to Protect Yourself

You don’t need to be a scientist to avoid these risks. Here’s what actually works:

- Keep a complete list of everything you take - prescriptions, over-the-counter meds, vitamins, herbs, even CBD. A 2020 study found this cuts interaction risks by 47%.

- Use one pharmacy. Chain pharmacies have systems that flag dangerous combinations. They prevent about 150,000 adverse events in the U.S. every year.

- Ask your doctor or pharmacist: “Could this interact with anything else I’m taking?” and “Are there foods or drinks I should avoid?” Mayo Clinic research shows this increases detection of risks by 63%.

- Avoid grapefruit juice if you’re on any prescription drug - unless your provider says it’s safe.

- Space out problematic meds. Take thyroid medicine and calcium supplements at least four hours apart. Same for iron and dairy.

What Your Provider Is Doing to Help

Hospitals and clinics aren’t ignoring this. Electronic health records now warn doctors about 85% of major interactions. But here’s the catch: doctors get so many alerts that they ignore nearly half of them. That’s called alert fatigue.

Pharmacists are stepping in. Medication therapy management - where a pharmacist reviews all your drugs - reduces adverse events by 22% in Medicare patients, according to CMS data. In fact, pharmacist-led reviews prevent over 1.2 million serious interactions every year in the U.S.

Tools like Lexicomp and Micromedex help providers check interactions in seconds. And now, the FDA requires new drugs to be tested for CYP enzyme effects. About 60% of approved drugs affect these enzymes in some way.

The Future: Personalized Medicine

Genetics play a bigger role than you think. About 5% of people are poor metabolizers of CYP2C19 - meaning they break down certain drugs very slowly. For them, even normal doses can be toxic. The FDA now includes pharmacogenomic info on 340 drug labels. Testing for these variations is becoming more common - and could cut interaction-related hospitalizations by up to 30% in the next decade.

Telehealth platforms now include built-in interaction checkers. By 2023, 78% of major U.S. health systems had added them. This isn’t science fiction - it’s happening now.

Bottom Line

Pharmacokinetic interactions aren’t rare. They’re common, dangerous, and often preventable. The key isn’t knowing every drug on the market. It’s being proactive. Keep your list updated. Talk to your pharmacist. Ask questions. Don’t assume a supplement is safe just because it’s natural. And never ignore a warning about grapefruit juice or dairy with your meds.

Your body is a complex system. Medications aren’t harmless. But with a little awareness, you can stay in control - and keep yourself safe.

What’s the difference between pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug interactions?

Pharmacokinetic interactions are about how your body moves the drug - absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. Pharmacodynamic interactions are about how the drugs affect your body together. For example, taking two sedatives might make you overly drowsy - that’s pharmacodynamic. One drug changing how fast another is broken down? That’s pharmacokinetic.

Can over-the-counter drugs cause serious interactions?

Absolutely. Common OTC drugs like ibuprofen, naproxen, antacids, and even cold medicines can interfere with prescription drugs. St. John’s Wort - sold as a supplement - can make birth control, antidepressants, and transplant drugs stop working. Always tell your pharmacist about everything you take, even if it’s “just a vitamin.”

Why is grapefruit juice so dangerous with medications?

Grapefruit juice blocks an enzyme in your gut called CYP3A4, which normally breaks down many drugs before they enter your bloodstream. When that enzyme is blocked, much more of the drug gets absorbed - sometimes two to five times the normal amount. This can turn a safe dose into a toxic one. The effect lasts up to 72 hours, so even eating grapefruit hours before your pill can be risky.

Are herbal supplements safe to take with my prescriptions?

No - not without checking. Supplements like St. John’s Wort, garlic, ginkgo, and echinacea can all interfere with medications. St. John’s Wort can reduce the effectiveness of antidepressants, blood thinners, and birth control. Garlic and ginkgo can increase bleeding risk with warfarin. There’s no safety guarantee just because something is “natural.” Always ask your pharmacist.

How do I know if I’m having a drug interaction?

Watch for sudden changes: unusual drowsiness, dizziness, rapid heartbeat, unexplained bruising or bleeding, nausea without cause, or confusion. If you start a new medication and feel worse - not better - it could be an interaction. Don’t wait. Call your doctor or pharmacist right away.

Should I stop taking a medication if I suspect an interaction?

Never stop a prescribed medication on your own. Stopping suddenly can be dangerous - especially for blood pressure, heart, or seizure drugs. Instead, contact your provider or pharmacist immediately. They can help you adjust the dose, switch medications, or space doses safely.

Is it safe to take my meds with food?

It depends. Some meds need food to be absorbed (like certain antibiotics or antifungals). Others need an empty stomach (like thyroid meds or some osteoporosis drugs). Calcium, iron, and dairy can block absorption of many drugs. Always check the label or ask your pharmacist how to take each medication - and stick to it.

Can alcohol interact with my medications?

Yes - and it’s more common than people think. Alcohol can increase drowsiness with sedatives, raise blood pressure with antidepressants, and cause liver damage when mixed with acetaminophen. Even moderate drinking can be risky. The old myth about metronidazole and alcohol causing severe reactions has been questioned, but alcohol still affects many drugs. When in doubt, avoid alcohol while on new medications.

Jan, 14 2026

Jan, 14 2026

Andrew Freeman

January 15, 2026 AT 21:35Vicky Zhang

January 17, 2026 AT 02:54Susie Deer

January 17, 2026 AT 16:39TooAfraid ToSay

January 17, 2026 AT 19:09Robert Way

January 18, 2026 AT 08:20Sarah Triphahn

January 20, 2026 AT 03:49Allison Deming

January 22, 2026 AT 02:58Jason Yan

January 23, 2026 AT 14:53Dylan Livingston

January 24, 2026 AT 20:57says haze

January 25, 2026 AT 21:05